Biography

Roots

Dvořák’s ancestors settled in Central Bohemia in the region around Kralupy nad Vltavou, north-west of the Bohemian capital, Prague. The region is home to the village of Nelahozeves, where the composer’s grandparents lived from the year 1818. Antonín Dvořák was born here on 8 September 1841 to Anna and František Dvořák, as the first of nine children. The family ran a business in house number 12, a cottage that had an inn on the ground floor. A fire broke out here in the summer of 1842 and the future composer was rescued by his father who carried him out to safety. All of Antonín’s predecessors were butchers or innkeepers, thus it was automatically assumed that the first-born child would inherit the business. In addition to the butcher’s trade the Dvořák family line cultivated another talent: a flair for music. However, music-making was merely regarded as a means to brighten up the daily routine and as a way to earn a little on the side. But it wasn’t long before everyone realised things would be different in Antonín’s case.

childhood

In music he far surpassed everyone else, so his father entrusted him to the care of Nelahozeves school teacher and musician Josef Spitz, in order that he develop his son’s skills further. Young Dvořák soon mastered the violin and entertained guests at village dances, and it wasn’t long before he gave his first solo appearance as a violinist in the local church serving the nearby village of Vepřek. Even so, during his childhood, Dvořák was still expected to help his father with the family business and prepare to take it over one day. His apprenticeship involved visits to local markets in the neighbourhood, where father and son would select livestock. He later described an incident from his young days where he led a head of wild cattle home from the village fair on a rope, whereupon the animal dragged him into a lake. At the time he is said to have vowed in a flood of tears that he was never going to be a butcher. It was also during this period that Dvořák first set eyes on the trains that would fascinate him his whole life. When he was nine years old he witnessed the construction of the railway which passed through Nelahozeves. The first steam train, a crowning achievement in technological progress at the time, passed through the village in the summer of 1851. It was probably these impressions from his childhood which ignited his future passion for everything associated with modern transport.

Zlonice

Shortly after finishing school, young Antonín was sent by his father to the nearby town of Zlonice, where their relatives lived. Thus, in 1853, at the age of twelve, Dvořák found himself under the supervision of Zlonice teacher and multi-instrumentalist Antonín Liehmann. Liehmann, an excellent musician in the vicinity, soon recognised an exceptional talent in young Dvořák and so he began to instruct him in the basics of harmony and playing organ, violin, and piano; later he also allowed Dvořák to play at Mass. It was during this time that Dvořák wrote his first compositions, short polkas. Since he invested much more of his time learning music than anything else, he began to fall behind with his German, a subject that would be essential to him as a future tradesman. So his father decided to send him to Česká Kamenice (Böhmisch Kamnitz), the majority of whose inhabitants spoke German, to spend a year living in a German-speaking family. Here Dvořák not only improved his German, but he also continued his music after making the acquaintance of the local regenschori, Franz Hanke, who permitted him to play the organ in the local church during Mass. Dvořák never did learn the butcher’s trade, since Liehmann finally managed to convince his father František that his son’s extraordinary talent deserved the consistent supervision and instruction that only a music institution could provide. Thus, in the autumn of 1857, 16-year-old Dvořák moved to Prague.

his own master

Young Dvořák was extremely short of money during the early stages of his career. For many years – until he got married – he lived with relatives and in rented rooms at various Prague addresses: Initially in his cousin’s flat in Dominikánská street, later with his father’s youngest sister on Karlovo náměstí, for about a year in Václavská street, and during this time he also had lodgings for one or two years on Senovážné náměstí. When he left the organ school he was not yet eighteen years of age and could no longer expect any financial support from his parents, particularly since his father’s business continued to deteriorate. He thus applied for the position of organist at St Henry’s church. He proved to be the best of the six candidates, but he was not accepted due to his lack of experience. Roughly during this same period he decided to accept the post of viola player in the Komzák Ensemble, a small orchestra which performed undemanding programmes at dances, in restaurants and at promenade concerts. When the Provisional Theatre opened in the autumn of 1862 the entire Komzák Ensemble was engaged as the core of the opera orchestra. Thus, for the next nine years or so, Dvořák performed the viola parts of operas by Verdi, Meyerbeer, Donizetti and others on a daily basis, often conducted by Bedřich Smetana. Nevertheless, this influx of music did not suffice and he studied a huge number of scores at home as well. His meagre income would not allow him to purchase any music, and so he generally borrowed scores from his friend, the composer and choirmaster Karel Bendl, whose flat he frequently visited in order to play on the piano.

studies

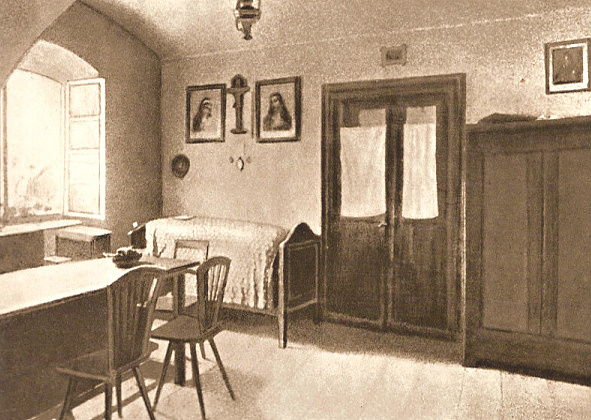

The decision had been made to send Dvořák to the Prague organ school. The Institute for Church Music, as the school was officially known, was located in Konviktská street in the Old Town and provided instruction in organ playing, harmony and counterpoint. The school did not have much in the way of facilities: it comprised three very basic classrooms within a dilapidated former Jesuit college, and the pupils only had one inferior organ at their disposal. These failings, however, were compensated for by the excellent teaching staff who were able to provide their students with solid foundations in music theory and practice. Alongside his studies at the organ school young Dvořák also attended a German school whose fourth year he completed in 1858. Not long after starting his education in the city he became a member of the Cecilian Association Orchestra, where he not only acquired valuable experience as an orchestral viola player, but he also began to familiarise himself with 19th century music. He graduated from the organ school in July 1859 with a public concert, at which he performed a Bach prelude and fugue and also two of his own works: Prelude in D major and Fugue in G minor. These are some of the first pieces by Dvořák to survive as autographs.

composer

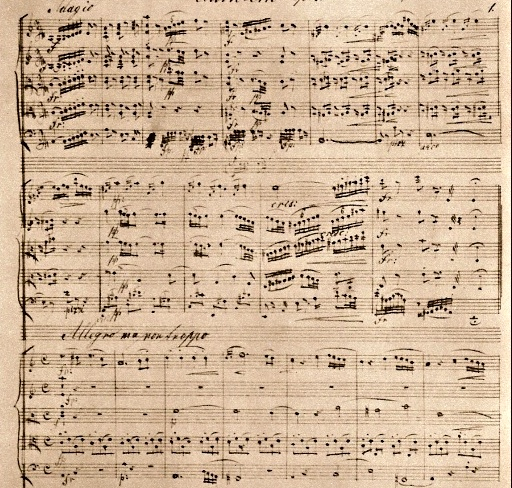

While Dvořák was engaged in detailed study of works by the great masters, he was already writing his own music. He probably wrote a large number of works during this time, none of which were performed; he was extremely self-critical and destroyed the majority of his scores. The first work he thought well enough of to assign it an opus number, thus officially embarking on his career as a composer, was String Quintet in A minor from 1861 (Dvořák was nineteen at the time); this was followed by String Quartet in A major, Op. 2. It wasn’t long before he tried his hand at a major musical form, producing his First symphony in the key of C minor with the subtitle “The Bells of Zlonice”, after which he immediately set about writing his extensive Symphony No. 2 in B flat major, which he completed within a mere two months. In the meantime he even managed to write his Cello Concerto in A major for a colleague in the orchestra – all this in cramped conditions living in a single rented room which he shared with several other lodgers.

ill-fated love

Dvořák’s pupil and son-in-law Josef Suk later reported – perhaps based on what the composer himself had said – that, around the year 1865, he had fallen for the charms of a young actress from the Provisional Theatre, Josefina Čermáková. His acquaintance with her was in a certain sense a defining moment in his personal life from that point on, since he later married her younger sister Anna (Mozart and Haydn experienced something similar). Not only did Dvořák and Josefina work in the same theatre, but the composer also encountered her during his visits to the Čermák family, whom he taught the piano on a regular basis. Dvořák expressed his love for the actress in a cycle of love songs entitled Cypresses, a musical setting of a collection of poems by Gustav Pfleger-Moravský. Josefina later married Count Václav Kounic but Dvořák maintained his affections for her and remained close friends with both of them his whole life. Dvořák returned to Cypresses on many occasions thereafter; its melodies feature in a number of the composer’s later works.

first successes

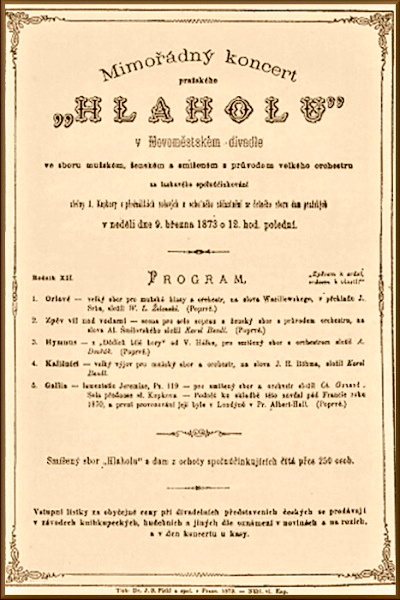

Dvořák’s engagement in the Provisional Theatre Orchestra provided him with a wealth of inspiration via the numerous opportunities to perform various world operatic works and as yet isolated examples of Czech opera, which probably played a major role in his decision to try his hand, after chamber and symphonic works, at writing opera as well. As a completely unknown composer without any means he could not afford to commission a new libretto, and so he used an earlier text, Alfred der Grosse, penned by the Neo-Romantic German poet Karl Theodor Körner. Dvorak’s first opera Alfred was never performed during his lifetime. He soon began work on his second opera, King and Collier, which upon completion he then offered to the Provisional Theatre. After several rehearsals, however, the score was returned to him as unplayable, in response to which Dvořák rewrote the entire opera to the same text. The second musical setting was now regarded as feasible, and Dvořák was able to present himself in public as an opera composer for the first time. The decisive factor in sealing the composer’s reputation on home soil, however, was the extraordinary success of the performance in March 1873 of the Hymn “The Heirs of White Mountain”, set to a text by Vítězslav Hálek. With this work the hitherto anonymous violist in the Provisional Theatre Orchestra established himself as an original composer with a promising future whose success on this occasion motivated him to continue his composition work. Encouraged by the enthusiastic reviews of the Hymn he then turned out one work after another: Symphonies No. 3 in E flat major and No. 4 in D minor, three string quartets, the one-act comic opera The Stubborn Lovers and a number of other pieces, some of which did not survive.

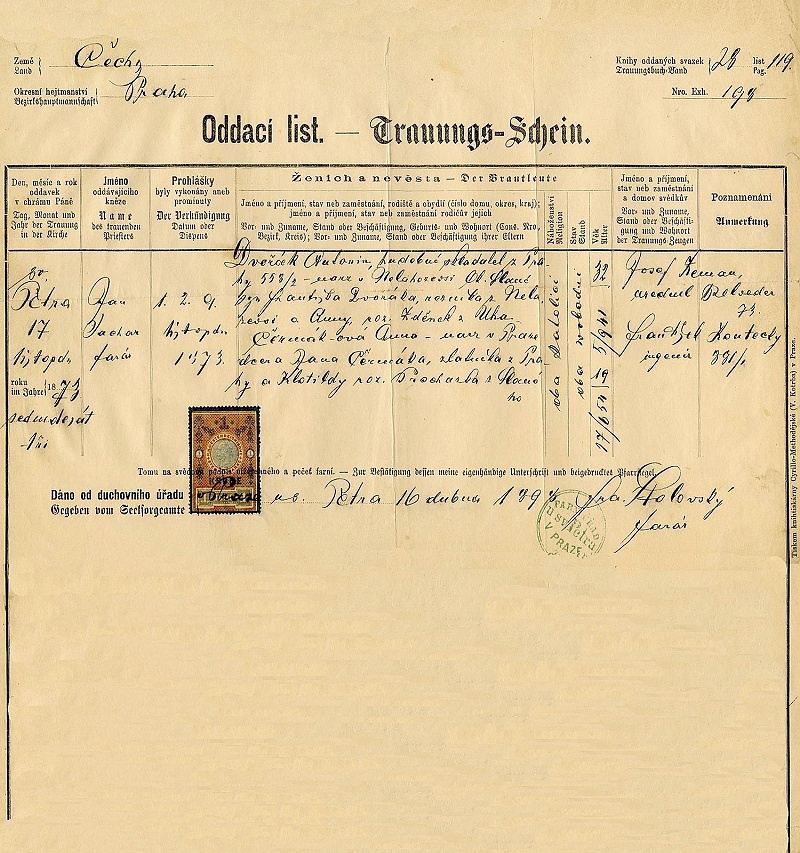

marriage

While Dvořák’s career as a composer was flourishing, major changes were also occurring in his private life as well. He continued teaching the piano in the Čermák family home and began to form a close relationship with Josefina’s younger sister Anna. Anna Čermáková shared his love of music – she played the piano and she was regarded as a fine singer, performing her husband’s works later on. The pair were married on 17 November 1873 in the church of St Peter; Dvořák was thirty-two and Anna thirteen years his junior. According to the laws of the time, Anna had not yet reached maturity by the date of the marriage, however, she was in her fourth month of pregnancy. The newly-weds initially lived with Anna’s mother Klotilda Čermákova but, after a few months, they moved to a modest flat in Na Rybníčku street. There Anna gave birth to her first-born son Otakar in April 1874, and it wasn’t long before the arrival of daughters Josefa and Růžena. The family had very little money, and their friends even arranged a collection for them. Anna contributed to the meagre household budget with the occasional fee earned from singing in Prague churches, both in the choir and as a soloist. At this time Dvořák decided to accept the post of organist at St Adalbert’s church, where he remained for three years. The family’s chief source of funding, however, was still income earned from private tuition.

financial independence

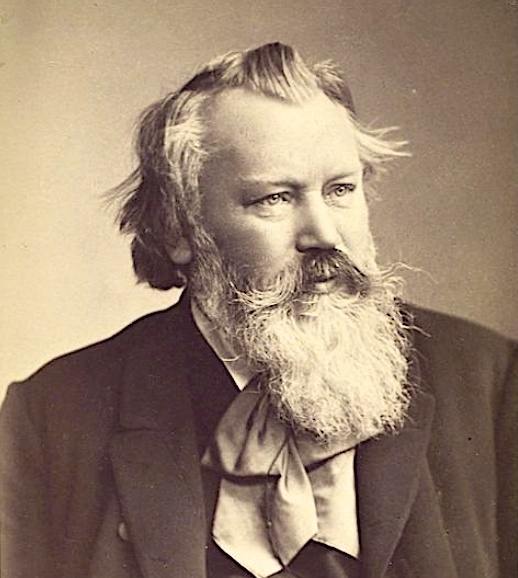

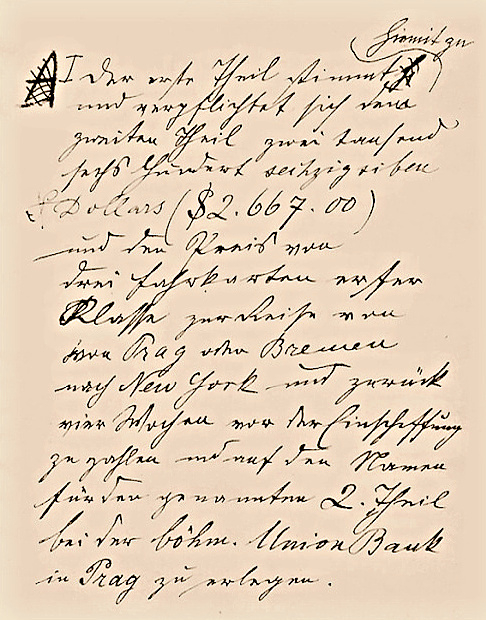

The situation changed at the beginning of 1875. Dvořák decided to apply for a state scholarship awarded each year to young impoverished artists who demonstrated exceptional talent. In addition to a document confirming his lack of means which Dvořák requested from the Prague municipal authorities, he enclosed his application for the scholarship together with the scores of his last two symphonies and other works, and sent all these together to the Ministry of Culture and Education in Vienna, which allocated the scholarships. He was awarded the highest possible grant of 400 gulden, which represented a fortune for the young family. Dvořák was also successful in subsequent years, winning the award five years in a row. The jury who decided which applicants would receive scholarships – from Dvořák’s second application onwards – also included Johannes Brahms, by then a noted figure. He had a great appreciation for Dvořák from the beginning and they later became lifelong friends. On Brahms’s recommendation, Dvořák also began having his works published by one of the most important German publishers, Fritz Simrock. The fees Dvořák received were initially very low, however, they gradually increased as the composer became more prominent.

across the border

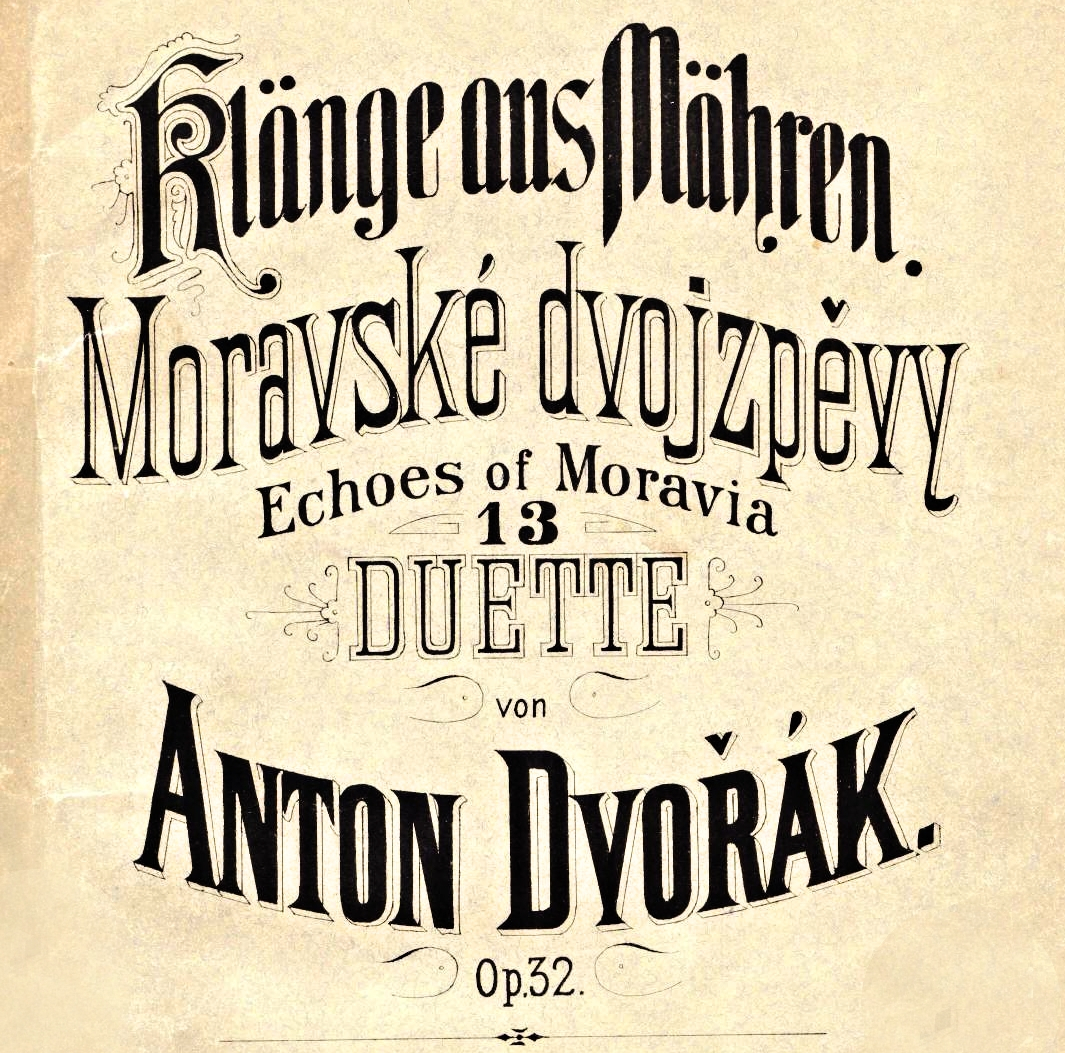

The following stage in Dvořák’s career was extremely productive; not only did the state scholarship enable him to focus much more on his composition work, but his contact with the major German publisher paved the way for important connections outside the country. None of this came a moment too soon: despite the huge number of works he had already written, Dvořák, now past the age of thirty, was still an unknown entity in the eyes of the public at large. In terms of his subsequent career as a composer, the most important works to come out of this period were his Moravian Duets and Slavonic Dances, which attracted the attention of the critics, for the most part in German-speaking territories. Apart from the duets, Dvořák turned out a whole series of other pieces, including the popular Serenade for Strings in E major, the Piano Quartet in D major and Fifth Symphony in F major.

family tragedy

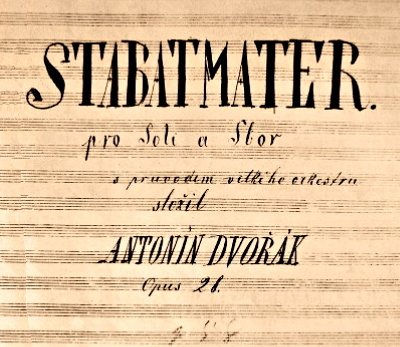

After this joyful period in Dvořák’s career which saw him extremely focused on his composition work, however, he suffered an unexpected blow. After the death of his daughter Josefa, who died two days after birth, his one-year-old daughter Růžena died under tragic circumstances (phosphorus poisoning) in August 1877; and, one month later, his son Otakar, then three-and-a-half years old, succumbed to smallpox. Within a short period Dvořák had lost all three of his children. After the death of the first child he wrote the piano version of what would become one of his most celebrated works: Stabat Mater. With the loss of another two children Dvořák returned once more to the text of the mediaeval Latin sequence describing the Virgin Mary’s suffering as she witnesses the Crucifixion of her Son; this was now the definitive orchestral version. The oratorio Stabat Mater contributed significantly to the composer’s international celebrity in years to come.

Slavic period

In order to try to forget the recent tragic events as quickly as possible and probably also because of their neighbours, whose piano playing disturbed the composer in his work, the Dvořáks moved from Na Rybníčku street to a new address, Žitná 10 (today 14), which became their permanent home. The following three years (c. 1878–1880) are known as Dvořák’s slavic period, characterised by a strong leaning towards the roots of Slav folk music and, at the same time, representing some of the composer’s most productive years. Music flavoured with Slavic colour and nuances was sought-after both in the Czech environment (given the patriotic fervour of the time), and beyond the country’s borders (for its “exoticism”). Dvořák produced a large number of works during a relatively short space of time, among them, further Moravian Duets, the Serenade for Wind Instruments in D minor, the three Slavonic Rhapsodies, a series of piano pieces, String Quartet No. 10, “Slavonic”, Czech Suite, and also the first series of the famous Slavonic Dances. These were followed by Symphony No. 6 in D major, which conductor Václav Talich later described as a work “pulsating with the blood of the Czech Lands”.

heading towards England

At the beginning of the 1880s Dvořák’s music found its way to a country traditionally host to all manner of musical geniuses and one of the most important music centres – England. From the time of Händel, the country had cultivated a strong tradition in the performance of oratorios and cantatas and, once discerning London audiences had been introduced to the Stabat Mater, the die was cast. Dvořák was invited to London, a visit which proved crucial for his entire subsequent career. Interest in his music continued to grow, English music institutions and festivals began to commission specific works, and hence the majority of the composer’s journeys across the Channel involved the premiere performance of a new work. This particularly concerned Symphony No. 7, written for London, the oratorio Saint Ludmila commissioned for the festival in Leeds, and the cantata The Spectre’s Bride and Requiem for the Birmingham festival. Dvořák travelled to the British Isles a total of nine times and each visit was a triumph both for the composer and for Czech music. His connections with England culminated in the conferral of an honorary degree from Cambridge University in June 1891.

Vysoká

Together with the recognition he was enjoying in European music circles (in addition to England, Dvořák’s works were also being performed in Vienna, Budapest, Leipzig, Berlin, and elsewhere), things were going extremely well in his private life as well. During the years 1878–1888 Dvořák and his wife had a succession of six healthy children who all survived into adulthood. Soon after the birth of their daughter Anna, the whole family was invited by Josefina Kounicová to visit her chateau in Vysoká u Příbramě which she had received as a wedding gift from her husband, Count Václav Kounic. Dvořák was so enchanted by Vysoká that he decided to purchase from his brother-in-law an old building with a garden at the other end of the village; this he had adapted to his family's needs. For the next twenty years the family spent their summers here and Dvořák wrote a large number of his works in Vysoká, many of which are among his most famous compositions.

American period

In 1891 Dvořák received an offer which would have fundamental consequences for his life and work: an invitation to the United States of America. The enterprising president of the National Conservatory of Music in New York, Jeanette Thurber, decided to raise the prestige of the school by offering the post of director to a leading figure in European music circles. The Czech maestro was chosen for this role. After much hesitation the composer finally signed a contract which obliged him to head the music institution and teach composition, and this for a salary that was thirty times higher than the amount the Prague Conservatoire was able to offer. At the beginning of the school year 1892/93 Dvořák sailed across the ocean to America where, apart from one break, he spent two and a half years. It wasn’t long before he brought all his feelings and impressions together in his legendary work: in January 1893 he started sketches for his Symphony No. 9 in E minor, subtitled “From the New World”. In the summer Dvořák and his family travelled for their holidays to the village of Spillville in the state of Iowa, where descendants of Czech emigrants live to this day. Here the composer felt quite at home. In a joyful frame of mind, within just a few days, he penned the sun-filled String Quartet No. 12 in F major, entitled “American”, which was immediately followed by String Quintet No. 3 in E flat major, works of unusual melodic invention. After his return to New York, he continued his teaching and also witnessed the triumphant premiere of the New World Symphony, which took place in Carnegie Hall on 16 December 1893. The composer felt that he needed to spend the following summer holidays in his homeland, in Vysoká. During this summer intermezzo he wrote a cycle of eight Humoresques for the piano. During the school year 1893/94 Dvořák created his most intimate work, Biblical Songs. In the last year of his stay in the United States the composer produced his celebrated Concerto for Cello and Orchestra in B minor.

back home

Upon his return from the United States, Dvořák resumed his teaching at the Prague Conservatoire, passing on his experience to future leading Czech composers Oskar Nedbal, Vítězslav Novák and Josef Suk, who married Dvořák’s oldest daughter Otilie a few years later. 1896 was an important year for Czech culture with the institution of a new orchestra which in subsequent years would become the most famous orchestra in the country: the Czech Philharmonic. As the most prominent living Czech composer, Antonín Dvořák was asked to conduct a programme of his own works at the orchestra’s inaugural concert in Rudolfinum.

mythical world

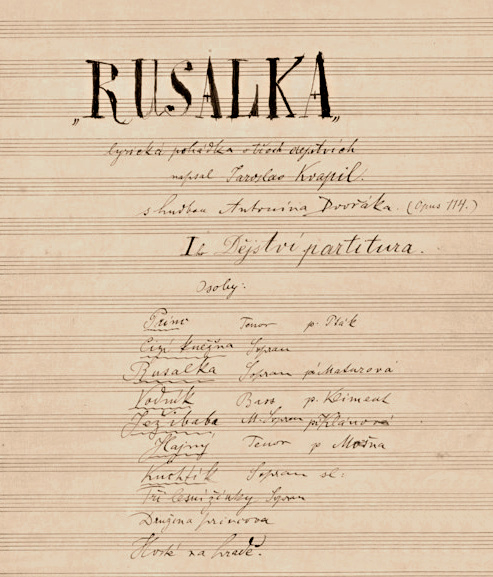

In the latter part of his career Dvořák’s music betrayed a shift towards the realm of myths and fairy tales. He first wrote four symphonic poems inspired by texts from the collection Bouquet by Karel Jaromír Erben, beginning with The Water Goblin, then The Noon Witch, The Golden Spinning Wheel and finally The Wild Dove. This collection is one of the composer’s few contributions to the programme music genre. Dvořák’s musical legacy concluded with three stage works. The first is the comic opera (arguably the composer’s most original) The Devil and Kate. After this came the composer’s most frequently performed opera, the lyrical Rusalka, whose premiere in 1901 was a pure triumph and assured him his rightful place in the opera repertoire as well (until now he had been regarded chiefly as an author of symphonic and chamber music). The very last work Dvořák wrote is the opera Armida, set in the exotic environment of the Orient. The premiere in March 1904 did not go as the composer would have wished, mostly due to shoddy preparation work on the part of the company. Dvořák’s frustration at the careless staging of the opera was compounded by health problems. With the onset of acute kidney pain he was forced to leave the theatre during the performance.

death

The renal colic Dvořák was suffering was complicated by a chill and then influenza, and his doctor prescribed bed rest. In the morning of 1 May he felt a little better, well enough to want to join his family for Sunday lunch. After having some soup, however, he felt ill and soon lost consciousness. The doctor was summoned immediately, but could only confirm that the composer had died; a stroke was cited as the official cause of death. A modern medical diagnosis, however, would probably have shown the cause of death to be pulmonary embolism, which the patient would have suffered after a prolonged period of bed rest.